Table of Contents

What do vegans eat for protein? Along with carbohydrates and fats, proteins are the third group of macronutrients in the diet. The building blocks of these complex molecules are called amino acids, nine of which are essential for a healthy adult and therefore must be obtained from food. Proteins from plants usually contain all the essential amino acids, making it possible to meet the requirements on a vegan diet. However, concentrations vary depending on the food. Therefore, it is recommended to combine vegan proteins in the form of protein-rich plant foods.

In general, official protein recommendations for adults are not very high, and most people consume more than this. Worldwide, 65 % of protein needs are met from plant sources (Young and Pellet, 1994), underscoring the importance of these foods in protein supply. For environmental and social reasons, scientists recommend reducing the amount of protein from animal sources, making it all the more important to know how to meet protein or essential amino acid needs from plant sources on a vegan diet (Day, 2013).

Functions

In general, proteins are important parts of human cells. The amino acids ingested with food must be converted to body protein in the organism. This process is called protein biosynthesis and happens with the help of 20 amino acids¹ that are considered proteinogenic.

The synthesized proteins are the building blocks of the body’s tissues. For example, muscles, tissues, and bones are largely composed of proteins. But enzymes, some hormones, and the immune system’s defense cells are also made of proteins. Proteins are the only substances with a mandatory nitrogen source in the molecule. Nitrogen is used to make other substances, such as genetic material (DNA). Proteins play a rather subordinate role in providing energy during periods of food abstinence. Preferably, carbohydrates and fats are used for oxidation and subsequent energy production. If there are not enough other energy sources available, however, proteins can be used as fuel or converted to carbohydrates to provide energy to the brain, for example.

Bioavailability

The bioavailability of amino acids affects protein quality, which can be assessed using several methods. A well-known one is the the biological value.

It describes how similar the amino acid composition of a food item is to that of the human body. The more similar it is, the less of it needs to be ingested to be converted into the body’s own material. The biological value has been determined using animal protein, which has a higher cellular affinity to humans and correspondingly higher bioavailability than vegan protein sources.

However, there are now more comprehensive methods for determining protein quality, such as the Protein Digestibility Corrected Amino Acid Score (PDCAAS) and the Digestible Indispensable Amino Acid Score (DIAAS). They are better suited to determine protein quality because they also incorporate protein digestibility. Currently, DIAAS is considered the most accurate method for determining protein quality (FAO, 2013).

What all of these methods have in common, is that the limiting amino acid plays the decisive role. The limiting amino acid is the amino acid that is present in the food in the lowest amount compared to the requirement. Foods of animal origin have, on average, a higher protein quality than those from vegan protein sources because they contain higher levels of essential amino acids.

However, most plants also contain all the essential amino acids for humans. Bioavailability can be increased by cleverly combining individual vegan protein sources. For example, the protein availability of grains (or grain products) is increased by the addition of legumes or oilseeds. With a well-balanced diet it is possible to meet amino acid requirements with vegan protein only. Soy protein is a very good vegan protein source: It is one of the few with a high protein quality as it has a biological value comparable to chicken egg white, which is used as a reference for determining biological value (Craig and Mangels, 2009).

Requirements and Status

Nutrition societies publish a calculated reference value for protein intake based on nitrogen balance studies, including a safety margin. The recommended intake is given as a function of body weight and is 0.8 g/kg body weight daily (DGE, 2016). Requirements are higher, for example, during growth, in infants and children, and during pregnancy (58 g/day) and lactation (63 g/day). In vegan diets, higher intakes could be necessary because the digestibility of protein from vegan food is lower than in mixed diets. However, there are currently no official recommendations for protein intake in vegan diets.

Scientific studies indicate that the amount recommended by most nutrition societies is only the minimum requirement, and that higher amounts (approximately 1.2–1.6 g/kg body weight) are necessary for everyone to reap additional health benefits. For the elderly and athletes, the requirement is even higher (Phillips et al., 2016).

Deficiency

On average, people in Western societies get (more than) enough protein. Chronic deficiency is virtually unknown in these countries. As long as energy needs are met, there is probably no need to worry about protein defiency. Protein requirements are significantly higher only during growth, and are usually overestimated during adulthood.

In developing countries, protein deficiency is more common, mainly due to general malnutrition or undernutrition. In children, the classic protein deficiency disease is kwashiorkor, which is associated with the typical symptoms of a protruding water belly, clouded consciousness, and edema, or water retention in the tissues.

In adults, protein deficiency results in a weakened immune system, since the body’s own defenses (immunoglobulins) are proteins. In addition, muscle protein can be degraded by under- or malnutrition, especially without physical activity and sports. In principle, a deficiency is only associated with general malnutrition and occurs in developing countries due to a lack of food supply. On the other hand, it can affect groups of people in industrialized countries who suffer from a physical or psychosomatic illness such as eating disorders.

Vegan Protein Sources

Proteins, just as carbohydrates and fats, are found in all vegan foods, just in different amounts and amino acid compositions. A varied isocaloric vegan diet can easily meet the need for proteins or amino acids.

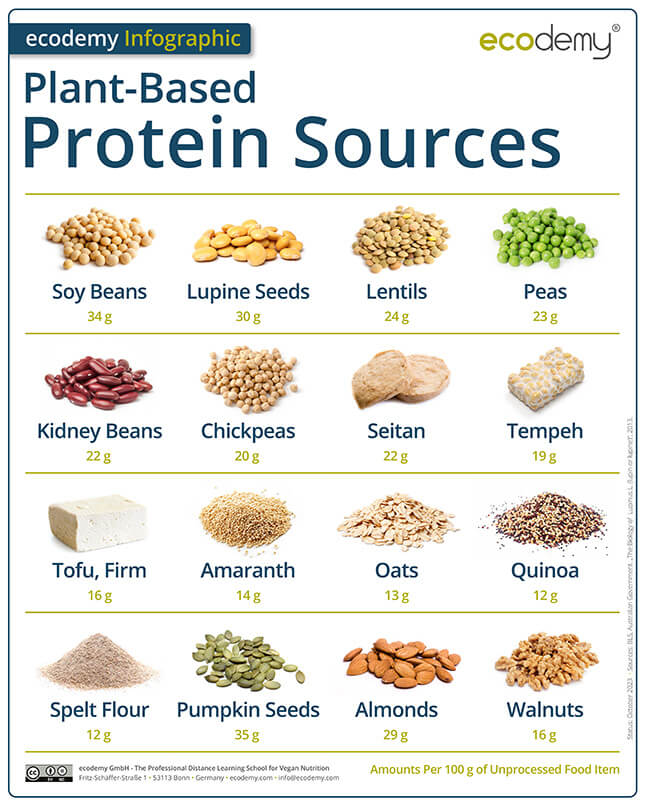

Legumes such as peas, lentils, and beans are excellent sources of plant protein. Soybeans, in particular, have an exceptionally high protein quality, comparable to foods of animal origin. Whole grains, whether ground or sprouted, also provide valuable amino acids. Pseudo grains (amaranth, buckwheat, quinoa), nuts, and seeds are also excellent sources of vegan protein. Similarly, sprouts and green leafy vegetables can also add to the intake of protein.

Table 1: Protein Content of Some Vegan Foods (BLS, USDA)

| Protein | |

|---|---|

| (g/100 g) | |

| Nuts and Oil Seeds | |

| pumpkin seeds | 35.5 |

| hemp seeds | 31.6 |

| sunflower seeds | 26.1 |

| almonds | 24.0 |

| flaxseeds | 22.3 |

| cashew seeds | 21.0 |

| pistachio | 20.8 |

| sesame | 20.9 |

| tahini | 17.8 |

| Brazil nuts | 17.0 |

| chia seeds | 16.5 |

| hazelnuts | 16.3 |

| walnuts | 16.1 |

| Legumes (and Products) | |

| tofu | 15.5 |

| soy beans, cooked | 15.2 |

| lentils, cooked | 9.4 |

| white beans, cooked | 9.6 |

| kidney beans, cooked | 9.4 |

| chickpeas, cooked | 9.0 |

| black beans, cooked | 8.9 |

| grean peas, cooked | 5.6 |

| silken tofu | 5.5 |

| soy milk | 3.5 |

| Grains and Pseudo Grains (and Products) | |

| amaranth, raw | 14.4 |

| oats | 13.2 |

| wholemeal spelt flour | 12.7 |

| quinoa, raw | 12.2 |

| couscous, raw | 11.7 |

| wholemeal wheat flour | 11.4 |

| millet, raw | 10.6 |

| buckwheat, raw | 9.8 |

| brown rice, raw | 7.8 |

| Vegetables and Salads | |

| cress | 4.2 |

| mushrooms | 4.1 |

| alfalfa sprouts | 4.0 |

| broccoli | 3.8 |

| spinach | 2.8 |

| potatoes | 1.9 |

| zucchini | 2.0 |

| cos lettuce | 1.6 |

| Swiss chard | 2.1 |

| lamb’s lettuce | 1.8 |

| head lettuce | 1.2 |

| celery | 1.2 |

By cleverly combining the above foods, the protein synthesis in the body can be increased by improving the amino acid spectrum. As you can see in figure 1, eating grains together with legumes or nuts ensures that lower amounts of essential amino acids in one food are excellently supplemented by the other. Whole grain bread with hummus or nut butter are practical examples. You probably do not necessarily need to combine these foods in one meal; eating a variety of foods from different vegan food groups throughout the day is sufficient.

Protein Status in a Vegan Diet

Several studies suggest that vegan people meet protein recommendations with intakes averaging 12 % of daily energy intake (Davey et al., 2003; Larsson and Johansson, 2002; Waldmann et al., 2003). This is lower than the intakes of people eating a mixed diet (15-17 %) and vegetarians, who derive about 13 % of their daily energy intake from protein (Davey et al., 2003). However, the latter two populations tend to have quite high protein intakes, especially from sources of animal origin. In figure 2, you can see some examples of vegan protein sources.

Conclusion

The best way to consume protein on a vegan diet is through an energy-adequate and balanced diet. Since all plant foods, especially the ones that are not highly processed, have a certain protein content, adequate amounts are consumed every day. Good sources of vegan protein include legumes (lentils, beans, peas), nuts and oilseeds, whole grains and pseudo grains, and green leafy vegetables and sprouts. By combining certain foods with varying essential amino acid content, protein utilization increases. This can be done, for example, with a meal of legumes and grains (humus and wholemeal bread).

As long as you meet your energy needs through mostly minimally-processed foods, protein needs can be met as a vegan.

The content of this article cannot and should not replace individualized vegan nutrition counseling. You can find expert help in your area or online in the International Directory of Vegan Nutritionists.

Background Knowledge

1Selenocysteine can be considered the 21st proteinogenic amino acid because it can be derived from the non-essential amino acid serine. The biosynthesis process is very different from other amino acids that are synthesized as “free amino acids”. These are not produced during protein biosynthesis (bound to tRNA). Therefore, selenocysteine is not a direct substrate for protein biosynthesis, but serine is. After binding to tRNA a hydroxyl group (OH) is exchanged with a selenol group (SeH) (serine is converted to selenocysteine).

Leave a Reply